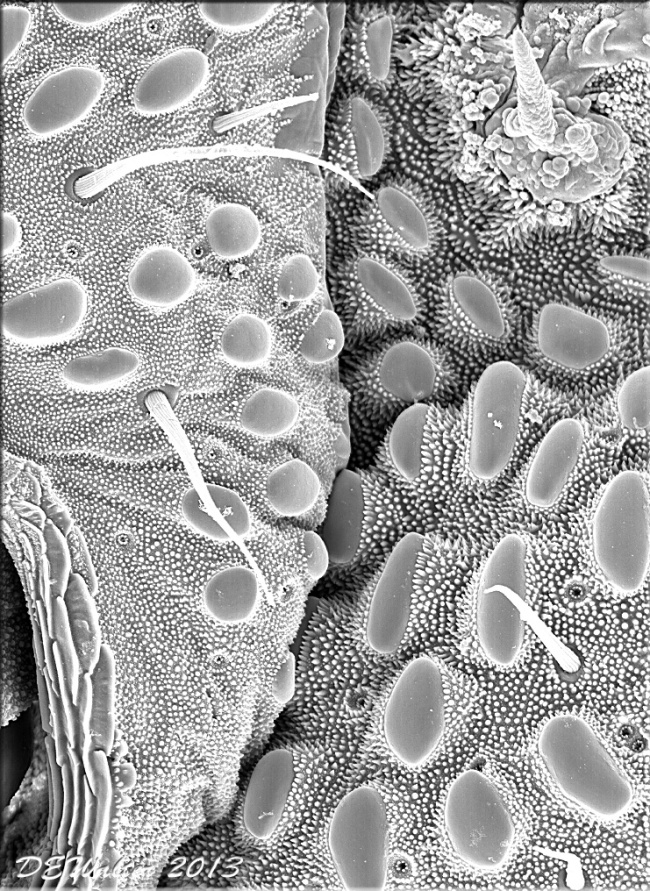

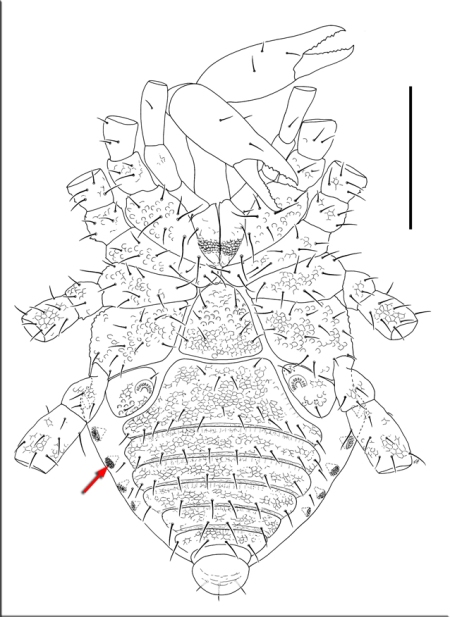

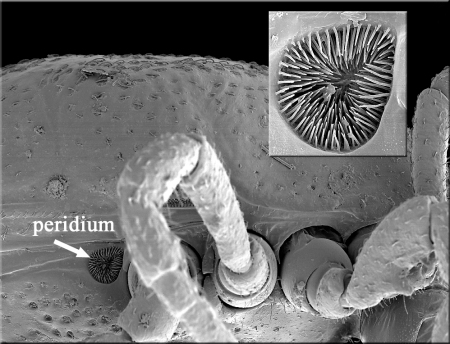

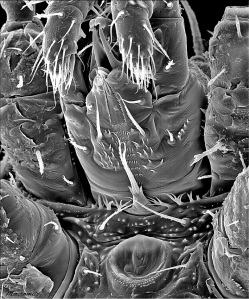

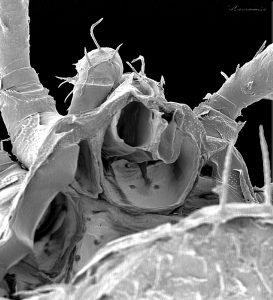

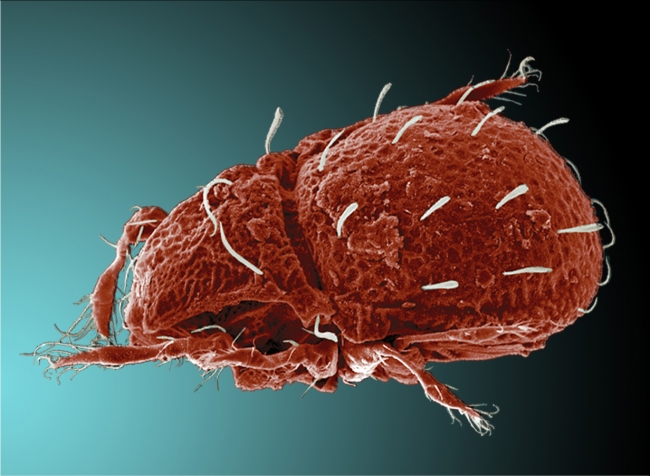

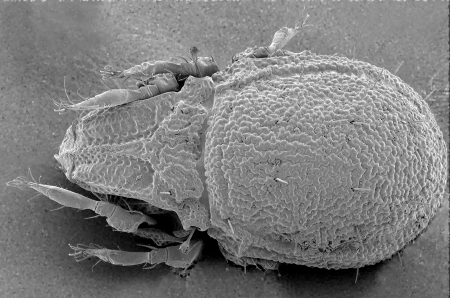

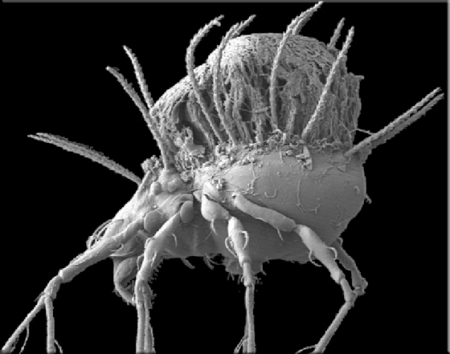

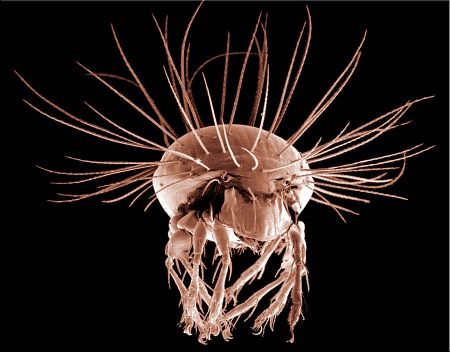

An anystid (possibly an Anystis) eating a scale insect (Photo Geoff Waite)

I was reading an essay on political cant by George Orwell yesterday, “Politics and the English Language” (1946), at Project Gutenberg Australia*. As one exercise he rewrote, into political obfuscation, a famous and lyrical passage from the Bible:

“I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favor to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth.” (Ecclesiastes 9:11 King James Version)

Almost always Orwell makes his points clearly and with passion. I now feel a bit chastised at my writing and terrified of using ‘dying metaphors’, ‘verbal false limbs’, ‘pretentious diction’ and ‘meaningless words’. I especially don’t want to use meaningless words.

That same day, I received a request for help with the etymology of a genus of mites, Anystis von Heyden, 1826. I was at a loss, my books were of no help, and Google failed. I’ve previously posted on the psychic perils of reading Karl von Heyden’s mind. Anystis seemed to be without meaning.

This morning, though, after a long walk taking poor pictures of macropods and beetles, the verse from Ecclesiastes bobbed-up in my memory along-side Anystidae – a family of famously swift runners. Common names include ‘whirligig mites’ in North America and ‘footballers’ in Australia (don’t ask me to explain Australian Rules Football, but even a few minutes of watching will convince you that the players in colourful jerseys spin around with abandon much like the mites). Could Anystis be a name, not from the Latin or Greek, but of something or someone fast in the past?

My friend Bruce Halliday (at what is left of the CSIRO at Black Mountain) had sent on a list of von Heyden genera and from my limited knowledge, his names indicated an interest in Greek history. For example, Cunaxa a genus of predatory mites may be a reference to the Battle of Cunaxa reported on by the Greek mercenary Xenophon.

With the proper modifiers, Google now came to the rescue with a passage from a delightful book on ‘Running through the Ages’ by Edward Seldon Sears: “The Spartan runner Anystis and Alexander the Great’s courtier Philonides both ran 148 miles (238 km) from Sicyon to Elis in a day.” (Sears 2001). This seems to be derived from Pliny in his Natural History, who thought this run (1305 stadia) was more impressive than the better-known dash of Philippides from Athens to Sparta (1140 stadia) to report on the battle of Marathon.

I take this race as strong inference of what von Heyden was thinking when he proposed the genus Anystis. Anyone who has watched these mites must be impressed with their speed, and although the ancient Anystis exhibited both speed and stamina, I now feel some confidence that I am using the generic name in a non-meaningless way.

References:

* http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300011h.html#part47

von Heyden, C. H. G. 1826. Versuch einer systematichen Einteilung der Acariden. Isis, 18, 608-613.

Sears, E.S. 2001. Running through the Ages. McFarland: Jefferson, NC.